CORAL WAY ELEMENTARY SCHOOL

In 1963, Miami’s Spanish-speaking immigrant community was growing. In response to the needs of those children, Coral Way Elementary became the first publicly-funded dual language two-way immersion program in the United States. As part of the program, both Spanish- and English-speaking children would learn in both languages. Becoming bilingual and biliterate.

Although some of their original methods changed, Coral Way’s visionary program has had lasting effects. The school is a celebrated bilingual institution in the community and beyond. It was recognized as “School of the Year” by the Spanish Consulate in 2018 and what started as a temporary “experiment,” continues to impact educational policy today. In 2019, there were more than 2,000 dual language programs across the US. In Florida alone, there were over 125.

The Coral Way Dual Language Experiment, a book authored by Dr. Maria Coady, will be released in fall 2019 (Multilingual Matters Publishers). It shares the story of Coral Way's extraordinary experiment using materials from the Coral Way Digital Collection, housed at the University of Florida George A. Smathers Libraries.

In 1959, Fidel Castro and the 26th of July movement took power in Cuba. As a direct result of the new regime’s radical changes, thousands of Cubans sought exile in the United States, and particularly Miami, Florida. Adding to the number of immigrants, were also more than 14,000 unaccompanied minors who came to the U.S. between 1960 and 1962 as part of Operation Peter Pan (Operación Pedro Pan).

With public resources straining, the U.S. established the Cuban Refugee Program in 1961. The Program included federal funds for public schools impacted by the increasing numbers of Cuban immigrants, as well as assistance for those immigrating with professional backgrounds. This perpetuated the “model minority” label associated with the early waves of Cuban immigrants.

Bilingual classes at Coral Way Elementary. 1960s.

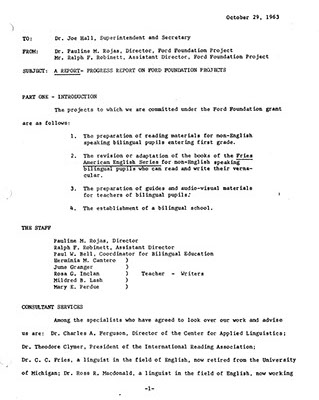

1961 | Ford Foundation

In 1961, Dade County Public Schools (DCPS) hired Dr. Pauline Martz Rojas as a consultant. Dr. Rojas created guidelines for Cuban refugee students known as the “Basic Program for Cuban Pupils.” In addition to the guidelines, Dr. Rojas recommended that DCPS submit a proposal to the Ford Foundation for financial assistance. DCPS Superintendent Joseph Hall and Dr. Rojas worked together to submit the proposal for “a comprehensive approach and medium term solutions to support Cuban students and American teachers.” The project was awarded $278,000 in 1962. Its two main objectives were “to create materials for teaching English, using the Fries series as a foundation for English as a Second Language (ESL) students and to prepare teachers for English-learning students.”

To achieve those objectives, Coral Way staff prepared reading materials for non-English speaking students. They created guides and audio-visual materials for teachers of bilingual students. They also revised or adapted books in the Fries American English Series. But most importantly they established the first bilingual school.

1962 | Teacher Preparation

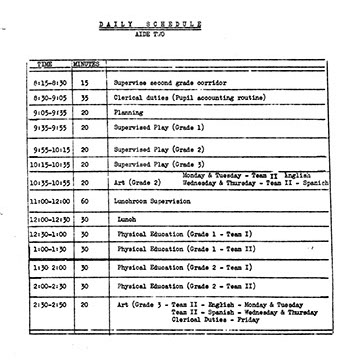

Coral Way classroom teachers were assigned Aides who were recently arrived bilingual Cuban teachers. Due to language and certification differences, their professional experience and training went unrecognized by Dade County Public Schools (now Miami-Dade County Public Schools). Aides worked alongside teachers to help Spanish-speaking children learn and adjust to life in the United States.

The Ford Foundation funded the Cuban Retraining Program through nearby University of Miami to give Cuban Aides the possibility to obtain their Florida teaching license. All 33 teachers that were accepted into the first round passed the state certification test.

1963 | Implementation

In fall 1963, Coral Way Elementary launched the bilingual program with twelve teachers and three teacher aides. The program was divided equally among three grade levels (first, second, and third grade) with four groups in each grade. Within each grade, there were two groups of native Spanish speakers and two groups of native English speakers.

Although the initial offering was small, the intention was to start a system that exposed students to bilingual education for the remainder of their elementary school experience.

1964-1965 | Evolving Program

Reaction to the program was mostly positive. People who supported it highlighted the benefits of cultural diversity exposure. Those who did not agree, spoke about the ways it was “un-American.” Yet the program continued to grow, gaining national and international attention.

Over time, the program evolved and changed. The dual language component expanded from the primary grades to include all levels at Coral Way, Kindergarten through 6th grade.

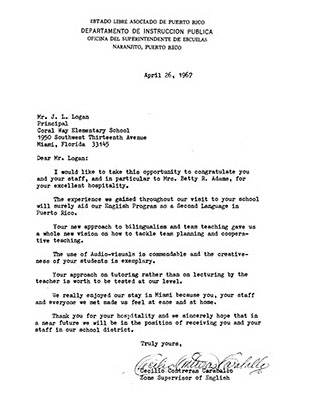

1966-1967 | Coral Way Visitors

The innovations at Coral Way Elementary attracted visitors from other school districts, counties, states, and even other countries. In 1966 Luis Morales Chua and Manuel Eduardo Rodriguez visited from Guatemala as well as Dr. Frances Klein from the University of California, Los Angeles. The following year, Cecilio Contreras Caraballo, a Zone Supervisor of English from Puerto Rico, visited Coral Way. Caraballo was looking for strategies he could use in Puerto Rico’s English as a Second Language Program. He later stated in a letter to Coral Way’s Principal Logan, “Your new approach to bilingualism and team teaching gave us a whole new vision on how to tackle team planning and cooperative teaching.”

1968 | Measuring Success

In 1968, Mabel Wilson Richardson was a teacher at Coral Way Elementary and simultaneously pursuing a PhD at the University of Miami. Her dissertation work included documentation of the Coral Way experiment. It is one of the only records of academic data from the early years of Coral Way’s program.

Mabel Wilson Richardson’s study compared the academic achievement of native Spanish speakers taught the basic school curriculum in English with those that were taught in both Spanish and English. There were three groups in the study. Each group included Spanish speaking and English speaking students in both the experimental and control schools. For evaluation, she used standardized Stanford Achievement and Intelligence tests already used in the county. To complement the test results, she also used a proficiency test in the second language – the Cooperative Inter-American Reading Tests (administered in May 1964, 1965, and 1966).

In studying Coral Way Elementary, Mabel Wilson Richardson sought to prove not that the bilingual program would be more effective than monolingual programs, but rather that English and Spanish speaking students would learn a second language by the end of the school year. She also found that:

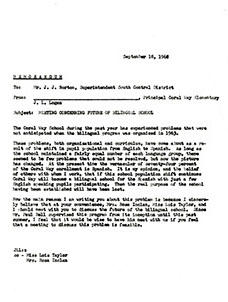

1968-1969 | Concerns About the Future

At the end of the 1967-1968 school year, Principal J. L. Logan wrote a letter to the Superintendent of the South Central District, J. J. Norton. In it he requested a meeting concerning the future of Coral Way as a bilingual school. He explained the problems that Coral Way had experienced that year. “These problems, both organizational and curriculum, have come about as a result of the shift in pupil population from English to Spanish.” When the program began in 1963, there was an equal number of English and Spanish speaking students. But as the situation in Cuba worsened, the number of refugees arriving in Miami increased. At the beginning of the 1968-1969 school year, Spanish speaking students were 74% of the school’s population. Principal Logan stated that “if this school population shift continues Coral Way will become a bilingual school for the Spanish with just a few English speaking pupils participating. Then the real purpose of the school having been established will have been lost.”

2019 | Present

Despite concerns, Coral Way Elementary was a successful dual language two-way immersion program. In 2004, the school expanded to include 7th and 8th grade and renamed Coral Way Bilingual K-8 Center. In 2005, Dr. Pablo Ortiz, principal of Coral Way, facilitated an International Spanish Academies Seminar in Seville, Spain. During the seminar Dr. Ortiz explained the goals of Coral Way are to provide students with the opportunity to:

This online exhibition is based on the exhibition of the same name that was presented at the University of Florida George A. Smathers Libraries,

October 21 – December 20, 2019.

Curated by Brittany Kester and Pia Molina | Designed by Lourdes Santamaría-Wheeler

Unless otherwise noted, all items are from the Coral Way Digital Collection, housed at the University of Florida George A. Smathers Libraries