Iconic and instantly recognizable, British illustrator John Tenniel’s tubular Alice laid the foundation for generations of artists to alter images of human beings to convey their impression of an author’s imaginary world. Some artists, such as Charles Robinson, took Tenniel’s image to the extreme of a snake-like head. Others, such as Rackham, deviated from Tenniel and created a new Alice (see here) whom people could love. A master of black and white illustration, George Cruikshank skipped along the fence between reality and imagination and influenced similar juxtapositions of the real, surreal, and completely fantastic in many of his successor artists, including Willy Pogány, Aubrey Beardsley, and Arthur Rackham. Walter Crane’s use of color and light in his Aesop’s Fables acknowledges the priority of reality in his artwork over imagination. At the same time, it is the jubilant mixture of exactitude of form with ebullient splashes of color that would find most favor among his successors. Even Beatrix Potter foreshadowed the movement to anthropomorphization of flora and fauna as she depicted Peter Rabbit leaning against a wall, feet crossed, and hand under chin, exactly as his human counterparts would have stood and ruminated.

|

|

|

|

Lewis Carroll and John Tenniel

Alice from Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland D. Appleton & Co. 1866 6 in. x 2 ¼ in. 23h949 Baldwin Library of Historical Children’s Literature |

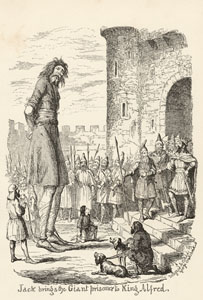

George Cruikshank

Jack brings the Giant Prisoner to King Alfred from George Cruikshank’s Fairy Book G. P. Putnam’s Sons 1897 5 ¾ in. x 4 ¼ in. 23h20894 Baldwin Library of Historical Children’s Literature |

Lewis Carroll and Charles Robinson

A large pigeon had flown into her face from Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland Cassell and Company, Ltd 1907 5 ½ in. x 4 in. 23h25151 Baldwin Library of Historical Children’s Literature |