African-American Writers on Lincoln

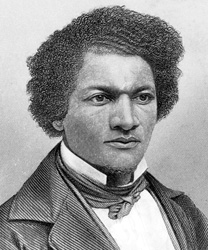

Among the works in Rare Books at the University of Florida are those by writers Frederick Douglass, William Wells Brown, and Elizabeth Keckley. Each was a close observer of Abraham Lincoln and expressed their views about his legacy.

Frederick Douglass (1818-1895) grew up in slavery in Maryland and escaped to freedom at about the age of twenty. By the time of the Civil War he had become famous as a writer and orator, as well as a prominent abolitionist. Although he praised Abraham Lincoln for the Emancipation Proclamation, his views on the president were complicated. He vigorously critiqued many of Lincoln’s policies, including the president’s proposal that freed slaves should be encouraged to leave the United States.

“The argument of Mr. Lincoln is that the difference between the white and black races renders it impossible for them to live in the same country without detriment to both. Colonization, therefore, he holds to be the duty and the interest of the colored people…. Illogical and unfair as Mr. Lincoln’s statements are, they are nevertheless quite in keeping with his whole course from the beginning of his administration up to this day, and confirm the painful conviction that though elected as an antislavery man by Republican and Abolition voters, Mr. Lincoln is quite a genuine representative of American prejudice and Negro hatred.”

(Douglass’ Monthly, September 1862)

Douglass was more favorably impressed with Lincoln at the time of the Emancipation Proclamation, though he felt it as a long time in coming.

“Common sense, the necessities of war, to say nothing of the dictation of justice and humanity have at last prevailed. We shout for joy that we live to record this righteous decree. Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States, Commander-in-Chief of the army and navy, in his own peculiar, cautious, forbearing and hesitating way, slow, but we hope sure, has, while the loyal heart was near breaking with despair, proclaimed and declared: ‘That on the first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any state or any designated part of a state, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the united states, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever, free.’”

(Douglass’ Monthly, October 1862)

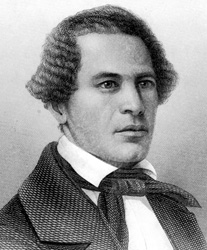

William Wells Brown (1814-1884) was born into slavery and spent the majority of his youth as a hired slave on steamboats. At the age of twenty, after many attempts, Brown finally escaped to freedom. He fled north and joined several antislavery organizations, ardently aligning himself with the abolitionist cause. Brown would become an extremely well-travelled and a widely popular antislavery orator, touring Europe in 1849 as a prominent speaker on abolitionist circuits. He returned to the states in 1854 to continue his lectures as well as focus on his writing. Self-educated and widely read, Brown is considered to be the author of the first African American novel (Clotel), the first published African American play (The Escape; or, A Leap of Freedom), the first African American European travelogue (Three Years in Europe), and the first history of African American military service in the Civil War (The Negro in the American Rebellion). In addition, his autobiography (Narrative of William W. Brown, a Fugitive Slave) was immensely popular and published in multiple languages.

The following is an excerpt of Brown’s recollection of publicly reciting the Emancipation Proclamation at Boston’s Tremont Temple on January 1, 1863:

“On the 22nd of September, 1862, President Lincoln sent forth his proclamation, warning the rebel states that he would proclaim emancipation to their slaves if such states did not return to the Union before the first day of the following January. Loud were the denunciations of the copperheads of the country, and all the stale arguments against negro emancipation … Delegation after delegation waited on the President, and urged postponement of emancipation …The friends of the negro were frightened; the negro himself trembled for fear that the cause would be lost…. They met on the last night in December, 1862… and waited patiently for the coming day, when they [the slaves] should become free. The forepart of the night was spent singing and payer, the following being sung several times:

‘No Compromise with Slavery!’ we hear the cheering sound, The road to peace and happiness ‘Old Abe’ at last has found; With earnest hearts and willing hands to stand by him we’re bound, While he sets the bondmen free!”

(The Negro in the American Rebellion, his heroism and fidelity, Boston: Lee & Shepard, 1867)

Elizabeth Keckley (1818-1907) was born a slave in Virginia, the child of a black house slave and a white Slave owner. As an adult, she used her skill as a seamstress to earn money and eventually purchased both her own freedom and that of her son’s for $1,200. In 1860, after taking up residence in Washington, she became personal dressmaker to Mary Todd Lincoln. Keckley’s war-time service included her founding of the Contraband Relief Association to aid freed slaves and union soldiers. She remained close to Mary Lincoln throughout Lincoln’s presidency.

In 1868 Keckley published her autobiography, probably with the aid of an unnamed co-author, and wrote candidly about her recollections of President Lincoln and his family:

“Mr. Lincoln, as everyone knows, was far from handsome. He was not admired for his graceful figure and finely molded face, but for the nobility of his soul and the greatness of his heart. His wife was different. He was wholly unselfish in every respect, and I believe that he loved the mother of his children very tenderly. He asked nothing but affection from her, but did not always receive it. When in one of her wayward impulsive moods, she was apt to say and do things that wounded him deeply…, but calm reflection never failed to bring [her] regret” (Behind the Scenes, or, Thirty Years a Slave and Four Years in the White House, New York: G.W. Carleton & Co, 1868:146-147).

This book led to her estrangement from Mary Todd Lincoln, who felt she was unfavorably portrayed.

Elizabeth Keckley Donates a Memento from the Lincoln Family

Dear Sir [Bishop Payne, D.D.]:

Allow me to donate certain valuable relics, to be exhibited for the benefit of Wilberforce University, where my son was educated, and whose life was sacrificed for liberty. These sacred relics were presented to me by Mrs. Lincoln, after the assassination of our beloved President. Learning that you were struggling to get means to complete the college that was burned on the day our great emancipator was assassinated, prompted me to donate, in trust to J.P. Ball [agent for Wilberforce College], the identical cloak and bonnet worn by Mrs. Lincoln on that eventful night. On the cloak can be seen the life-blood of Abraham Lincoln. This cloak could not be purchased from me, though many have been the offers for it. I deemed it too sacred to sell, but donate it for the cause of educating the four millions of slaves liberated by our President, whose private character I revere. You well know that I had every change to learn the true man, being constantly in the White House during his whole administration... This and many other relics, I hope you will receive in the name of the Lincoln fund. I also donate the dress worn by Mrs. Lincoln at the last inaugural address of President Lincoln. Please receive these from,

Your sister in Christ,

L. Keckley

(Behind the Scenes, 366-368)

Text by Rachel Walton