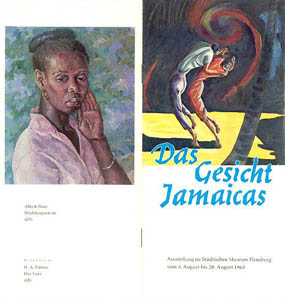

View the images and the layout from the original Face of Jamaica catalogue.

The exhibition’s German sponsor, Norbert Lorck-Schierning of the rum importer H.H. Pott wanted to guarantee the show’s “authenticity” and refrained from influencing the choice of works. Instead, Jamaica’s Minister of Development and Welfare, Edward Seaga set up a selection committee that invited collectors and artists to submit their works. In addition to paintings, drawings and sculptures, Jamaica also sent craft items, for example straw- and wood-work and embroidery, and a small selection of photographs to Germany. Barrington Watson, who was then Director of Studies at the Jamaica School of Art and Crafts, and later the painter Karl Parboosingh accompanied the exhibition on its journey.

The works ranged from naturalistic landscapes and portraits to a small number of abstracts. There were examples from academically trained artists, some of which displaying clear European or North American stylistic and formal influences, and works by untutored artists.

Based on Jamaican critic Norman Rae’s suggestion the selected works were divided into three categories, work, play and worship. Even though the large majority of portraits, abstracts, land- or cityscapes cannot be classified in any of the three stereotypical groups successfully, the Flensburg catalogue’s layout underlines the three-tiered division: Anna-Maria Hendriks’ Pocomania Meeting (“worship”) is placed opposite to Gaston Tabois’ Road Repair (“work”); and Palmer’s Faβroller (“work”) is juxtaposed with a photograph of a drum (“play” and/or “worship”).

While the Jamaican organisers announced to send the “cream of Jamaican art” to Flensburg, Lorck-Schierning believed it was not the purpose of the show to present an art collection of international standard but to introduce the audience to the “emotional world” of an “awakening people.” Consequently, standards of art criticism were of little importance to the German organisers, while, in much the same way as the Jamaican organisers, the understanding of art in the service of cultural education and national development, albeit romantically conceptualised, had higher priority.

The romantic stereotype of the island of Jamaica is viewed in the article entitled “A Beautiful Country, a Young People”. Its unknown author draws on the exhibition’s simplistic separation into the three categories work, play and worship. The author renders Jamaica as an exotic attraction, a carefree and light hearted young country without a history or traditions, constructed as the complete opposite of a presumably cultured Europe. He argues that the exhibition’s purpose was to introduce the German audience to a world of “powerful awakening, of work and play” and maintained that “...a young people, free of traditions” should be connected with “our culture, rich in traditions, but simultaneously burdened by the same."

With regards to the selection of works, in Face of Jamaica there was little evidence of a Jamaican past beyond the heyday of the nationalist movement in the late 1930s. Edna Manley's 1935 sculpture Negro Aroused, a symbol of the nationalist movement, was the oldest work in the exhibition.

* Reproduction, including downloading of works is prohibited by copyright laws and international conventions without the express written permission of the artists.