Animals in Jewish, Christian, and Islamic Illustrations from the Middle Ages

L’Apocalypse de Saint-Sever, Facsimile of MS Latin 8878 de la Bibliothèque Nationale (1078 CE)

1943. Paris: Éditions de Cluny

15 in. x 11.5 in.

096.1M693a Oversize

Rare Books Collection, Special & Area Studies Collections, George A. Smathers Libraries

The breathtaking imagery of the Apocalypse, or Book of Revelation, provided great inspiration for medieval commentators and illustrators. One of the most famous commentaries on the Apocalypse, known as the “Beatus” was composed by Saint Beatus of Liébana, an eighth century theologian from Northern Spain. The term “Beatus” nowadays refers to the 26 illuminated manuscript editions of this work held in libraries around the world. The text was reproduced in the early Middle Ages in order to educate and indoctrinate the clergy, and in Spain it came to be regarded as a symbol of Christian resistance to the Muslim Arabs who dominated much of the Iberian Peninsula during that period.

The Beatus of Saint Sever, displayed here in facsimile, is the most sumptuously illustrated of all the known Beatus manuscripts. Its illustrations were produced in the 11th century by Stephanus Garsia in the monastery of Saint-Sever in Gascony. Although it was produced outside of the Iberian Peninsula, it still followed the Spanish

tradition and is distinctive for its blend of Western and Mozarabic artistic influences.

The image on display shows a peacock with a serpent in its mouth. The peacock was used allegorically in Christian art to represent immortality. This association of ideas was derived from ancient lore which claimed that the flesh of the peacock did not decay. The peacock came to be associated also with the resurrection of Christ because of the way its old feathers are shed and replaced with a newer and brighter plumage. The serpent, or snake, is one of the oldest and most widely used mythological symbols in literature and art, and typically came to represent Satan in Christian iconography. The theme of the battle between the bird and snake, representing the triumph of good over evil, was present in antiquity and continued through to the Middle Ages.

The Cloisters Apocalypse, Facsimile of a manuscript from Normandy, France (c. 1330 CE)

1971. Metropolitan Museum of Art

12.5 in. x 9 in.

BS2822.5.C58 D48

Rare Books Collection, Special & Area Studies Collections, George A. Smathers Libraries

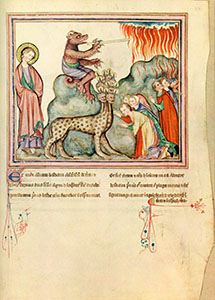

This Cloisters Apocalypse is an imaginatively illustrated version of the Revelation of St. John from the 14th century. Such apocalypses were extremely popular and used by the clergy and laity throughout the Middle-Ages. The textual version of the Cloisters Apocalypse is based on an earlier 13th century English manuscript, the Lambeth Apocalypse; yet the two are strikingly different in terms of their illumination. In the Lambeth Apocalypse the terror of the Last Days is reflected in gruesome artistic renderings. The Cloisters artist, however, is much more restrained, and some of the grotesques, or drolleries, in the outer borders are even humorous. The imaginary beasts on display here are the Beast of the Sea and the Beast of the Earth uniting to subdue the Saints according to the text in Revelation 13:7-13. The image is more colorful and exotic than frightening, with the Beast of the Earth sitting human-like wrapped in cloth atop a mountain. In the margins, the drolleries include a faintly penned figure with a beard and, on the opposite side, a beast with fangs and a malevolent tongue forms a support for a queen’s head. Other drolleries in the Cloisters Apocalypse include quite natural-looking, well-executed drawings of beasts that appear to have been copied from a bestiary.

The Luttrell Psalter: a facsimile, Facsimile of British Library MS Add. 42130 (c. 1320-1340 CE)

2006. London: The British Library

14 in. x 9.75 in.

ND3357.L8L86 2006 Oversize

Rare Books Collection, Special & Area Studies Collections, George A. Smathers Libraries

The Psalter emerged in the early Middle Ages as a distinct work comprising the Book of Psalms and other devotional material. The Luttrell Psalter, commissioned by wealthy English landowner, Geoffrey Luttrell in the 14th century, is one of the most celebrated examples of a Psalter due to its richly colored illuminations and striking images.

The artist’s handiwork is most notable for the great creativity and wit he exercised in the creation of the many grotesque figures that illuminate the borders of the text. These strange hybrid beasts were formed out of various combinations of human heads, animal bodies and plant tails. The grotesques, or drolleries, in the borders do not appear to relate to anything mentioned in the body of the work and therefore must have been a product of the artist’s imagination. They may have supplied a sense of incongruity which not only amused the reader but also served a didactic purpose: a reminder that bestial behavior can be subdued through contemplation of the message in the main text or central image. Thus, in the medieval mind, the corporeal world inhabited the border space while the Divine resided in the realm of the sacred text or miniature.

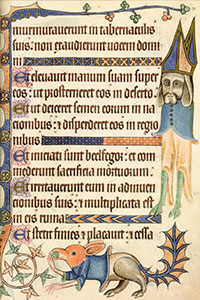

Displayed here in facsimile is ff.192 illustrating Psalm 105, which refers to the Israelites’ sojourn in Egypt and the plagues. The illustrator has provided border decorations with large grotesques: a strange creature on the right with long ears and a semi-human head wearing a Bishop’s mitre, as well as a mouse-like beast with human hands, hoofed legs and a webbed tail along the lower edge.