Animals in Jewish, Christian, and Islamic Illustrations from the Middle Ages

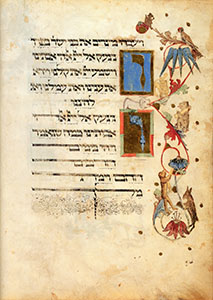

Barcelona Haggadah, Facsimile of British Library MS. Add. 14761, Catalonia (14th century CE)

1992. London: Facsimile Editions

10.5 in. x 8 in.

Isser and Rae Price Library of Judaica, Special & Area Studies Collections, George A. Smathers Libraries

This page from the Barcelona Haggadah contains unexpected animal imagery that reverses the traditional depiction of the hare hunt found in contemporary Christian manuscripts. The hare hunt was a popular activity around Easter (which coincides with Passover), and the hare itself was a symbol of fertility and rebirth in both Christian and Jewish texts. Yet, in the Barcelona Haggadah a hare dressed in robes places a stick on a dog’s head. The idea of the hare subduing the dog reverses the role of the hunter and the hunted or, in the Jewish mind, the persecutor and persecuted. In the same illustration, a swine offers the hare a cup of wine. In Christian art, the pig is associated with negative connotations: gluttony and materialism. Here too, the depiction of a pig offering the ritual Paschal wine no doubt represents Jewish reservations about alcoholic excess.

The Barcelona Haggadah is one of the finest illuminated Hebrew manuscripts from the Middle Ages. This copy, with its acute attention to detail, is widely regarded as an outstanding example of facsimile production.

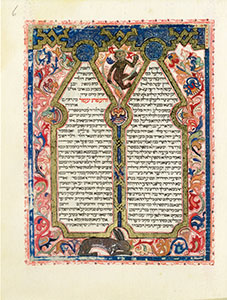

Ashkenazi Haggadah, Facsimile of Hebrew manuscript of the mid-15th century

from the collections of the British Library (c. 1460 CE)

1985. New York: H. N. Abrams

15.25 in. x 11 in.

BM675.P4 Z5233 1985

Isser and Rae Price Library of Judaica, Special & Area Studies Collections, George A. Smathers Libraries

Created in 15th century Germany, the Ashkenazi Haggadah was richly illuminated by Joel Ben Simeon, a scribe and illuminator whose name appears on eleven surviving manuscripts. Ben Simeon’s colored pen-drawings were heavily influenced by the prevailing Florentine style.

The animals in the margins displayed on folio 13b include a squirrel, bird, lion, dog and hare. They do not bear any relation to the subject matter of the text, which is compiled from Exodus and Deuteronomy, but are all elements of the medieval hunting scene. The hare hunt is one of the most popular themes in Christian manuscripts, but it is also found in many illustrated haggadot (pl.). Some commentators have drawn a parallel between the Hebrew mnemonic YaKNeHaz, which reminded the reader of the sequence of events in the Passover seder for a Saturday night, and the German phrase jag den Has which meant “hunt the hare.” Other commentators have seen the appearance of the hare hunt in haggadot as symbolic of the fate of the Jews of Europe around Easter time.

The Kennicott Bible, Facsimile leaves of Bodleian Library MS Kennicott 1, ff. 6 (1476 CE)

1985. London: Facsimile Editions

11.7 in. x 8.3 in.

Isser and Rae Price Library of Judaica, Special & Area Studies Collections, George A. Smathers Libraries

This facsimile (folio 6) from The Kennicott Bible provide an excellent example of the ways in which a medieval Jewish artist combined Islamic, Christian and popular motifs to create one of the most lavishly illuminated Hebrew Bibles produced in Spain. The artist-illuminator, known as Joseph Ibn Hayyim, signed his name in an extraordinary colophon, using large letters constructed from zoomorphic and anthropomorphic designs. The scribe was normally considered the most significant member of the book production team, so it is quite unexpected to find the illuminator’s signature, let alone rendered with such grandiosity.

More than a quarter of The Kennicott Bible’s 922 pages are illuminated with rich colors and burnished gold and silver leaf. The folios displayed here betray the strong influence of the Islamic decorative arts, as well as the geometric designs of Islamic architecture, on the artist. The borders around the text are rendered as Islamic style horseshoe arches, and the floral flourishes resemble those found in Qur’anic manuscripts. The beasts in the margins, including peacocks, hares, dogs, and an amusingly dressed monkey playing a pipe, are similar to those found in contemporary Christian works. Rather than attempting to produce educative illustrations to expound the text, Ibn Hayyim drew heavily on the iconography of the surrounding culture in a clear attempt to please and amuse the client who had commissioned the work.